Benjamin Cleary Fitzpatrick

#IrishPeatlands #Remediation #EnvironmentalJustice #JustTransition

The peatlands of Ireland have a long and rich history of providing the country with a reliable source of fuel, steady employment, and economic growth. Centuries ago, peatlands had little value and were generally associated poverty until people began to exploit them for agricultural purposes and eventually fuel extraction which occurred later on in the nineteenth century (Clarke, 2017). Once the potential of peatlands to produce fuel was recognised, they were utilized to their full extent with companies such as Bord Na Mona purchasing them for bog extraction, building factories to burn peat for energy as seen in the image below, and subsequently creating the Irish peat industry.

Images 1: Portarlington power station in the early 1950’s. Source: Bord Na Mona, (2023).

Continuous extraction over time has resulted in the non-renewable peatlands either becoming diminished or replaced with renewable sources of fuel. As a result of this along with Ireland’s renewable energy goals, Bord Na Mona now intends to remediate the peatlands that they own so that they can be restored to their former status as wetlands filled with flora and fauna or continue to fuel the country through other forms of energy extraction. While this sounds like a good thing, remediation efforts can cause serious issues if they are not handled correctly. In this blog post I want to explain how Bord Na Mona plans to remediate Ireland’s peatlands, where this can go wrong, and what the benefits of remediation are.

How the remediation of peatlands can have negative implications and cause conflict.

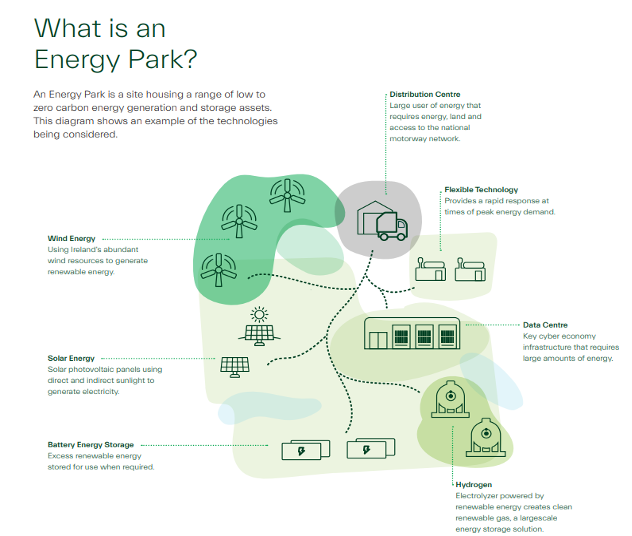

Remediation can be defined as the restoration, rebuilding or repurposing of exploited landscapes that have been damaged over time such as peatlands or industrial mines. While this sounds like an inherently noble goal with little room for malice, remediation can have dire consequences if the people responsible for the effort do not work with local populations by taking their opinion into account or if they ignore the wider contexts that the damaged landscape has endured over time (Beckett and Keeling, 2018). Working with all groups that are affected by remediation methods ensures environmental justice, which is the idea that any project which effects the environment does not impact a particular group of people or community unevenly and that any risk stemming from these efforts are distributed fairly (Mohai et al., 2009). As for Ireland’s peat bogs, this image below exhibits one purpose for the land that Bord Na Mona intends to remediate so that they can still provide energy in different ways.

Image 2: Bord Na Mona’s remediation vision for peatlands in counties Meath, Westmeath, and Offaly. Source: Bord Na Mona, (2021a).

This remediation plan is marketed as an environmentally friendly, green, and clean transition from non-renewable peat energy to renewable forms of energy. While this may be true, there are questions to consider when organising these remediation efforts. Whose values and interests are represented in these visions of restoring the landscape? What will happen to the workers currently employed by the peat industry? Have Bord Na Mona considered the implications of peatland remediation on roughly 20,000 households (Bullock et al., 2012) that still rely on peat fuel? These are just some of the questions that I will evaluate to examine how remediation can be a fair and prosperous for everyone.

Can Bord Na Mona maintain environmental justice for workers while remediating Irelands peatlands.

In order to remediate Ireland’s peatlands while remaining environmentally just, there are a few goals to consider. Firstly, Bord Na Mona must ensure a just transition for everyone affected both directly and indirectly by the peat industry’s transition to renewable energy. This means that the people who depend on Irish peatlands for employment would be eased through the remediation process in order to lessen and compensate for any impacts to their way of life as there is a high probability that this process will have both short- and long-term socio-economic effects for them (Banerjee and Schuitema, 2023). To do this would admittedly take a lot of time and resources from Bord Na Mona, both of which they may not have or may not want to spend. So far there has been little progress made in creating a just transition from the peat industry. In 2017 Bord Na Mona’s remediation process left 125 unemployed after the decision to close the Littleton peat factory in Tipperary (Bord Na Mona, 2018). Here is an image of the facility shortly before it ceased its operations.

Image 3: Littleton peat factory in Thurles, Tipperary. Source: Thurles Information, (2017).

I understand that a just transition requires a lot of time, finance, the ability to understand the context/history of a region as well co-operation with local populations (Mercier, 2020) and it is made difficult when the government is quickly striving for renewable energy. However, it is ultimately the responsibility of Bord Na Mona to ensure that these losses of unemployment do not become a regular occurrence. In my opinion these losses are likely to happen again since the new energy parks are expected to incorporate wind farms, solar power, and other forms of renewable energy (Mulvey, 2020) that require significantly less human labour to operate.

Can Bord Na Mona maintain environmental justice for peat dependent households while remediating Irelands peatlands.

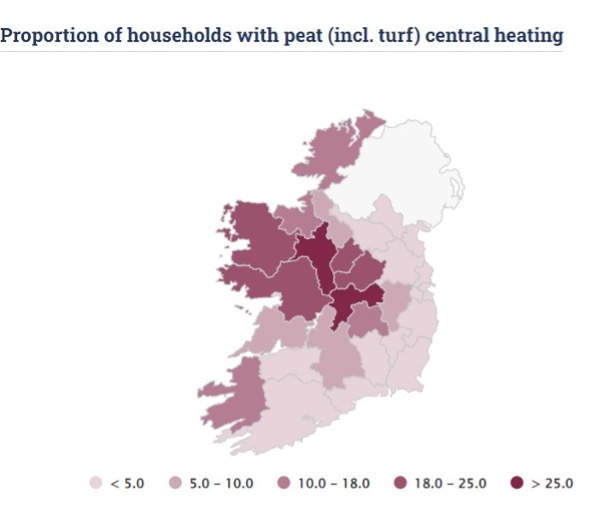

Another major impact of Irish peatland remediation is that older houses that rely on peat for heating and other usages will be left with an ultimatum. They will either have to implement a new system to fuel their homes or move elsewhere. You might think that households still using peat energy are a thing of the past but this is untrue. The Central Statistics Office (2017a) affirms that “Peat (including turf) was used by only 5.3% of households nationally for heating, however it was used by 23.6% of households in the Midlands. In Offaly, 37.9% of central heating systems in households used peat”. I have displayed this figure in the image below to give readers a better sense of scale.

Image 4: Percentage of Irish households that are reliant on peat. Source: Central Statistics Office, (2017b).

With this information in mind, the question is can Bord Na Mona compensate these households for the expense of a new heating system. Installing a biomass heat production system to suit an Irish household can cost anywhere between €10,000-€30,000, whereas the installation of a gas boiler may vary from €1500-€8000, while an oil boiler is in the range of €2000-€10,000 (Jones and Styles, 2007). These costs are not cheap, but they also do not include the cost of installing heat administration systems such as radiators (Jones and Styles, 2007) and that inflation has risen since sixteen years ago when this research was conducted. Bord Na Mona are a semi state company meaning that they have minimal government funding and are more interested in profit margins instead of helping the public. Therefore, it is extremely unlikely that they have the power to retrofit all these households with new heating systems even if they wanted to.

The benefits of remediating Ireland’s peatlands.

In order to critically evaluate the remediation of Irish peatlands it is only fair to point out the positive implications that come with it. One important thing to remember is that the peatlands of Ireland are being remediated in numerous ways. While I have discussed the remediation process that will result in renewable energy parks, Bord Na Mona also plans to remediate over 8,000 hectares of peatlands back to their natural roots as wetlands filled with biodiversity (Bord Na Mona, 2021b). They can accomplish this by removing the water drainage pipes that were originally installed so that the bog can naturally rewet itself over time. The image below shows this natural process in action.

Image 3: Irish peatland rewetting process. Source: Hurson, (2021).

Rewetting peatlands is of great benefit for two reasons. Firstly, it allows for the native plant and animal species that once thrived there to return once more, thus increasing biodiversity in the regions (Buckley et al., 2023). Secondly, returning peatlands back to the wetlands they once were allows for them to fulfil their original purpose of trapping and temporarily storing carbon, thus offsetting Irish carbon emissions into the atmosphere while also helping us reach our EU targets (Bresnihan and Brodie 2023). The final benefit that I want to mention is perhaps the most obvious. Peat is a non-renewable fossil fuel, meaning that when it is burned to provide energy it also releases carbon into the atmosphere. Achieving the goal of moving away from peat as a form of energy to more renewable ways will lessen Ireland’s contribution to global warming and consequently climate change. For more information about the importance of rewetting our peatlands and the benefits that stem from this procedure, please watch this interesting video on YouTube by Earth Horizon (2019).

Conclusion

While the remediation of Irish peatlands was inevitable given the current climate crisis and it does possess its merits, there also are many negative implications to consider. Many people hear about this remediation process and think of it is as an inherently good thing as we are switching from non-renewable fossil fuels to clean energy. Although remediation can lead to increased levels of peatland biodiversity as well as lowering our carbon emissions, this naïve outlook can be dangerous as it disregards the potential problems caused by peatland remediation. These include a loss of employment in the peat industry and households that are fuelled by peat being left vulnerable. This is not to say that I believe we should not remediate peatlands. Remediation can be done correctly once decision makers consider the opinions of all communities who will be affected. If we all work together, I am certain that we can recreate Irish peatlands in a way that is environmentally just for everyone.

Bibliography

Banerjee, A. and Schuitema, G. (2023). Spatial justice as a prerequisite for a just transition in rural areas? The case study from the Irish peatlands. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space [online]. 41(6), 1096 1112. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/23996544231173210 (accessed 14 December 2023).

Beckett, C. and Keeling, A. (2018). Rethinking remediation: mine reclamation, environmental justice, and relations of care. Local Environment [online]. 24(3), 216–230. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2018.1557127 (accessed 13 December 2023).

Bresnihan, P. and Brodie, P. (2023). Data sinks, carbon services: Waste, storage and energy cultures on Ireland’s peat bogs. New Media & Society, 25(2), 361–383. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221149948 (accessed 19 December 2023).

Buckley, Y.M., Farrell, C.A., Donohue, I., Gaughran, A., Gorman, C.E., McKeon, C.M., Stout, J.C. and Torsney, A. (2023). Reconciling climate action with the need for biodiversity protection, restoration and rehabilitation. Science of The Total Environment [online]. 857. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.159316 (accessed 19 December 2023).

Bullock, C.H., Collier, M.J. and Convery, F. (2012). Peatlands, their economic value and priorities for their future management – The example of Ireland. Land Use Policy [online]. 29(4), 921–928. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.01.010 (accessed 13 December 2023).

Bord Na Mona (2018) Annual Report 2018. Ireland: Bord Na Mona.

Bord Na Mona (2021a) Energy Park diagram [online photograph]. Available at: https://bnmenergypark.ie/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/BNM_EnergyPark_Brochure02_AW.pdf (accessed 13 December 2023).

Bord Na Mona. (2021b). Peatlands Restoration. [online] Available at: https://www.bordnamona.ie/peatlands/peatland-restoration/#:~:text=In%20the%20past%2C%20some%20peatlands,them%20to%20peat%2Dforming%20conditions (accessed 17 December 2023).

Bord Na Mona (2023) Portarlington power station [online photograph]. Available at: https://www.bordnamonalivinghistory.ie/timeline/1950s/ (accessed 11 December 2023).

Central Statistics Office (2017a) Private households by type of central heating by county, 2016 [online]. Available at: https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-rsdgi/regionalsdgsireland2017/env/ (accessed 16 December 2023).

Central Statistics Office (2017b) Proportion of households with peat (incl. turf) central heating [online photograph]. Available at: https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-rsdgi/regionalsdgsireland2017/env/ (accessed 16 December 2023).

Clarke, Donal (2017) Brief History of the Peat Industry in Ireland [online]. Available at: https://www.bordnamonalivinghistory.ie/article-detail/brief-history-of-the-peat-industry-in-ireland/#:~:text=From%20the%2017th%20century%20there,of%20turf%20as%20a%20fuel (accessed 11 December 2023).

Earth Horizon. (2019) Peatland Legacy (Saving Ireland’s Peatlands) EE17 EP4 . Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AfBRx9D87Js (accessed 20 December 2023).

Hurson, N. (2021) Rewetting Peatlands [online photograph]. Available at: https://www.farmersjournal.ie/news/news/rewetting-bogs-has-potential-to-improve-drinking-water-quality-report-613699 (accessed 17 December 2023).

Jones, M.B. and Styles, D. (2007). Current and future financial competitiveness of electricity and heat from energy crops: A case study from Ireland. Energy Policy [online]. 35(8), 4355–4367. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2007.02.035 (accessed 17 December 2023).

Mercier, S. (2020) Four Case Studies on Just Transition: Lessons for Ireland. Report number 15, Ireland: National Economic and Social Council.

Mohai, P., Pellow, D. and Roberts, J.T. (2009). Environmental justice. Annual Review of Environment and Resources [online]. 34(1), 405–430. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-082508-094348 (accessed 13 December 2023).

Mulvey, K. (2020) JUST TRANSITION PROGRESS REPORT. Dublin: Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications.

Thurles Information (2017) Littleton Peat Briquette Factory in Thurles, County Tipperary [online photograph]. Available at: https://www.thurles.info/2017/05/04/bord-na-mona-briquette-factory-to-cease-operations/ (accessed 14 December 2023).